Sludge management

Sewer and/or latrine construction is not enough to control the public health and environmental hazards of excreta. Latrine and septic/interceptor tank contents are collectively referred to as fecal sludge and require attention before their emptying and release to the environment. In addition to the “usual” sewage sludge from municipal wastewater treatment plants, the collection treatment and disposal of sludge from on-site sanitation systems must also be considered.

Characteristics of fecal sludge can differ widely from household to household, from city to city, and obviously from country to country. Public and community toilets add another dimension of uncertainty to questions about the chemical and biological quality of fecal sludge. In addition, vibrant cottage industries or other industrial activities will affect the quality and quantity of sludge to be managed.

Awareness and political will are needed at various levels of government to promote sustained improvements in fecal sludge management. Municipal or entrepreneurial bodies must be in place or be developed, to provide effective fecal sludge collection, haulage and treatment services. Such services needs both practical regulation, and enforcement of that regulation, from both financial and technical points of view.

In some cases cartels for sludge management arise, and households must pay exorbitant rates for the service; in others, there is no mechanism in place to ensure that, once collected, the sludge is safely deposited at a treatment works or landfill.

Contents

[hide]- 1 An array of tools from which stakeholders can choose include:

- 2 Incorporating faecal sludge management (FSM) into planning

- 3 Financial Analysis of FSM Options: Guiding public investment decisions

- 4 FSM technologies: Solar steam sterilizer

- 5 Field experiences

- 6 Sludge management links

- 7 Acknowledgements

An array of tools from which stakeholders can choose include:

- Systematic planning based on stakeholder identification and coordination (integrated with urban sanitation planning);

- Regulations on services provision and management procedures;

- Fee structuring and money fluxes (flux reversal !);

- Management and regulation of emptying services performed by private entrepreneurs (including realistic enforcement schemes against clandestine dumping in the nearest drain or ditch);

- Rules to secure a competitive market;

- Appropriate treatment options; and

- Securing the market for biosolids sale.

Incorporating faecal sludge management (FSM) into planning

in Sub-Saharan Africa:

Enhancing the Value Chain

Some questions to consider:

- Who's going to collect sludge from pits and septic tanks?

- What's going to happen to the sludge collected locally?

- Treatment, reuse, disposal: where is sludge eventually taken?

- Financing FSM: who's going to pay for all this?

Integrated sanitation planning needs to take into account both the situation now (i.e. existing sanitation facilities and infrastructure) and the expected situation in the future. In some cases, a centralised approach may prove to be the most cost-effective. But in many cases, the required level of investment for a centralised system is not feasible, and it may be more appropriate to adopt decentralised management solutions for collection and treatment of faecal sludge, probably centred around incremental improvement of existing FSM solutions.

Integrated sanitation planning also implies a need to look at cross-sectoral issues. In addition to the need to improve systems for excreta disposal, there is often a parallel need to improve systems for drainage and greywater disposal: many low-income communities are in low-lying areas that are prone to flooding, and problematic to serve because of high housing densities. A key question for integrated sanitation planning is whether it is more cost effective to design and install systems that have multiple functions, or to adapt separate systems for different types of waste management.

Financial Analysis of FSM Options: Guiding public investment decisions

There is a need firstly to prioritise where investment is most necessary, and secondly to assess the most cost-effective way of achieving the desired level of service. There are physical considerations that affect whether or not a particular type of sanitation system is technically viable: but in many situations, more than one technology may be feasible. So financial analysis of sanitation options is a core element of sanitation planning, and more specifically of FSM planning.

Financial tools are used to identify the most cost-effective sanitation solutions on the basis of life-cycle analysis taking into account all costs incurred and revenues generated over the total lifespan of an investment. As well as capital investment (CAPEX), capital maintenance costs (CAPMANEX), and operational and maintenance costs (OPEX), and the expected revenue streams from sanitation services, the financial analysis should take into consideration factors like the cost of land and different planning horizons, and should also consider the concerns of the different stakeholders, including (of course) users.

The main outcomes of the analysis, for each candidate solution considered, will be:

- how much users will be expected to pay for services (user charges or sanitation tax)

- what up-front capital investments are required

- net present value of different options

- whether there is a need for a subsidy

Financial analysis of this type provides a firm basis for guiding and coordinating investment by municipal governments, national governments and donors; and provides a common framework so that different investments and interventions are coordinated in a logical manner. As part of its ongoing FSM work in five countries, WUSP is currently developing an easy-to-use district-level tool called "Value-driven FSM", designed to assist municipal planners in making sanitation investment decisions. IWA is likewise strongly committed to developing the capacity of sanitation planners, through a wide-ranging programme of publications, events, training activities and peer-to-peer knowledge transfer.

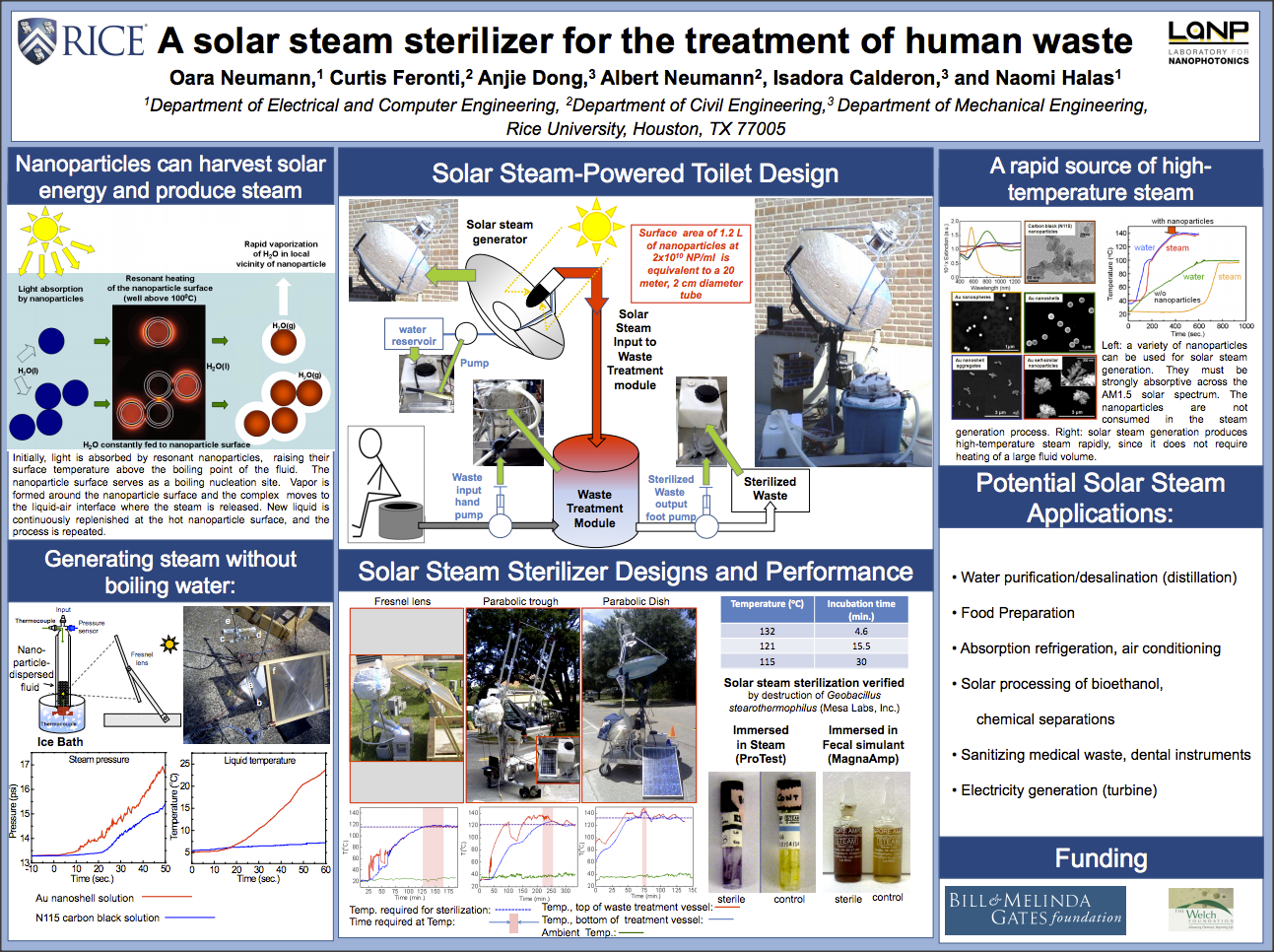

FSM technologies: Solar steam sterilizer

INFO & POSTER (download): A solar steam sterilizer for the treatment of human waste.

Field experiences

Dutch WASH Alliance in Hararghe & Dire Dawa |

WASH Media Forum |

Creating an enabling environment for WASH |

Sustainable Sanitation systems in communities |

Sludge management links

- Sangeeta Chowdhry and Doulaye Kone, Business Analysis of Fecal Sludge Management: Emptying and Transportation Services in Africa and Asia. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, September 2012.

- Teddy Nakato. FUEL POTENTIAL OF FAECAL SLUDGE: Calorific value results from Uganda, Ghana, and Senegal. Eawag, Sandec, Dakar University, Senegal, and Waste Enterprisers Ltd.

- Chandran, K., Murray, A. Fecal sludge-fed biodiesel plants: The next-generation urban sanitation facility. Kartik Chandran Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, USA. 2013

- Nelson, K. Safe sludge: The disinfection of latrine faecal sludge with ammonia naturally present in excreta. Regents of the University of California at Berkeley, USA. 2013.

- Mbéguéré, M. Structuring of the fecal sludge market for the benefit of poor households in Dakar, Senegal (ONAS). Senegal National Sanitation Utility (ONAS), Senegal. 2013.

- Menon, M. H. Landscape Study of Potential Investment Funds for Fecal Sludge and Resource Recovery in India. Consultancy report commissioned by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, USA. 2012.

- Rojas, F. Living without sanitary sewers in Latin America: The business of collecting fecal sludge in four Latin American cities. World Bank, Water and Sanitation Program (WSP), Latin America and the Caribbean, 2012.

Acknowledgements

- Choose Fecal Sludge Management Option. The World Bank.

- INTEGRATING FAECAL SLUDGE MANAGEMENT (FSM) INTO URBAN SANITATION PLANNING: Discussion Paper1 for WSUP/IWA workshop at AfricaSan 3, Kigali 19th July 2011, 10:00-13:00. IWA / WSUP.