Costs of WASH Service Delivery - Introduction

The costs of water, sanitation and hygiene services include expenditure on construction of water and sanitation systems, operation and maintenance and eventual rehabilitation of infrastructure. It also includes training and support to service providers, cost of capital, and expenditures for monitoring, planning and policy making. They are often referred to as life cycle costs; the costs of delivering water, sanitation and hygiene services indefinitely to a specific population in a particular geographic area, forever.

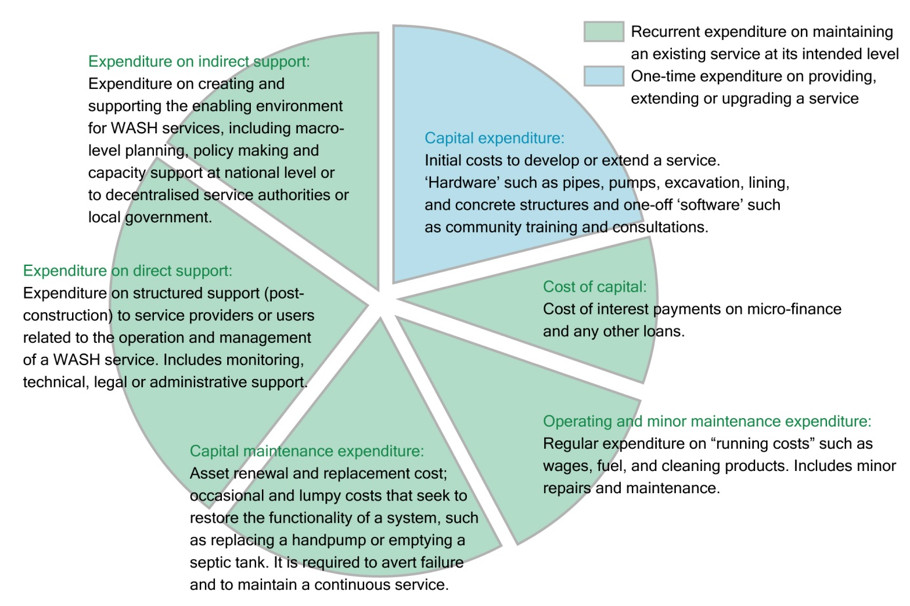

Life cycle costs are divided into six categories (see figure 1 below). These six categories are related to onetime expenditures on providing or upgrading a service, also known as capital expenditure (in green in figure 1) and recurrent expenditures (in blue in figure 1) on maintaining a service at its intended level.

Figure 1. Life cycle cost components

ANIMATION

Capital Expenditure (CapEx) is the costs of providing a water or sanitation service to users where there was no service before; or of substantially increasing the level of services received by users. It includes the capital invested in the first time construction of water and sanitation systems such as concrete structures, wells, pumps, pipes or toilets prior to implementation of the service. Capital expenditure can also include expenditures to improve or expand existing water or sanitation systems.

Recurrent expenditures consist of the following categories of expenditures:

Operations and minor maintenance expenditure (OpEx) covers the costs for operating and maintaining water and sanitation systems such as labour, fuel, electricity, chemicals, cleaning products for latrines etc.

Capital maintenance expenditure (CapManEx) is the cost of replacement or rehabilitation of water and sanitation infrastructure in order to keep service delivery on-going.

Cost of capital (CoC) is the expense of financing a programme or project and includes interest on loans and the cost of tying up scarce capital. In the case of private sector investment, the cost of capital includes what should be a ‘fair profit’, to be distributed as dividends.

Expenditure on direct support (ExpDS) includes expenditure on post-construction activities directed at local stakeholders, users or user groups. It is the cost of ensuring local government staff have the capacity and resources to repair broken systems and monitor service delivery.

Expenditure on indirect support (ExpIDS) includes government national level planning and policy making, plus developing and maintaining frameworks and institutional arrangements and capacity building for professionals and technicians. Expenditures on indirect support are not tied to a particular programme or project.

Examples

World Bank-RWSN Webinar life cycle costing

In this webinar on life cycle costing, Catarina Fonseca, IRC senior Programme Officer and the WASHCost project director, explains the life cycle cost components. This webinar was part of the World Bank-RWSN Webinar 7, May 15 2012.

Cost benchmarks

Based on research from the WASHCost project, the one-time capital expenditure for preparing and installing a borehole and handpump (at 2011 prices) range from US$ 20 per person to just over US$ 60 per person (see table 1). For small piped schemes, including mechanised boreholes, benchmark costs range from US$ 30 to just over US$ 130 per person. For intermediate and larger schemes benchmark capital costs vary widely from US$ 20 to US$ 152 per person. Recurrent costs benchmarks range from US$ 3 to US$ 6 per person per year for boreholes and handpumps, and from US$ 3 to US$ 15 per person per year for piped schemes.

Table 1. Capital and recurrent expenditure benchmarks for a basic level of water services

| Cost component | Primary formal water source in area of intervention | Cost range US$ (2011) [min-max] |

| Total capital expenditure (per person) | Borehole and handpump | 20-61 |

| Small schemes (serving less than 500 people) or medium schemes (serving between 500-5000 people) including: mechanised boreholes, single town schemes, multi-town schemes and mixed, piped supply. | 30-131 | |

| Intermediate (5,001-15,000 or larger: more than 15,001) | 20-152 | |

| Total recurrent expenditure (per person, per year) | Borehole and handpump | 3-6 |

| All piped schemes | 3-15 |

Source: IRC, 2012.

The costs as shown in table 1 are based on the provision of a basic level of water service, as defined by WASHCost. A basic service implies that the following criteria have been realised by the majority of the population in the service area: People access a minimum of 20 litres per person per day, of acceptable quality (judged by user perception and country standards) from an improved source which functions at least 350 days a year without a serious breakdown, spending no more than 30 minutes per day per round trip (including waiting time).

Based on research from the WASHCost project, the cost of preparing and building a traditional pit latrine that can provide a basic level of service ranges from US$ 7-26 (at 2011 prices) (see table 2).

The cost of a pit latrine with a concrete slab, or of a VIP latrine ranges from US$ 36 to more than US$ 350. The benchmark costs of pour-flush or septic tank latrines range between US$ 90-360 (rounded).

Recurrent expenditure range from US$ 1.5 for low-cost pit latrines per person per year to US$ 11.5 per person per year for the most expensive pour-flush or septic tank latrines.

Table 2. Capital and recurrent expenditure benchmarks for a basic level of sanitation services

| Cost component | Primary formal water source in area of intervention | Cost range US$ (2011) [min-max] |

| Total capital expenditure (per latrine) | Traditional pit latrine with an impermeable slab (made often from local materials) | 7-26 |

| Pit latrine with a concrete impermeable slab, or VIP type latrine with concrete superstructures (with ventilation pipe and screen to reduce odours and flies) | 36-358 | |

| Pour-flush or septic-tank latrine, often with a concrete or brick-lined pit/tank with sealed impermeable slab, inluding a flushable pan. | 92-358 | |

| Total capital expenditure (per person, per year) | Traditional pit latrine with an impermeable slab (made often from local materials) | 1.5-4.0 |

| VIP type latrines | 2.5-8.5 | |

| Pour-flush or septic-tank latrines | 3.5-11.5 |

Source: IRC, 2012.

The costs as shown in table 2 are based on the provision of a basic level of sanitation service, as defined by WASHCost. A basic service implies that all the following criteria have been realised by the majority of the population in the service area: At least some members of the household use a latrine with an impermeable slab at the house, in the compound or shared with neighbours. The latrine is clean even if it may require high user effort for pit emptying and other long term maintenance. The disposal of sludge is safe and the use of the latrine does not result in problematic environmental impact.

For both water and sanitation cost benchmarks (IRC, 2012):

- If expenditure is lower than the minimum range, then there is higher risk of reduced service levels or long-term failure.

- If expenditure is higher than the maximum range, an affordability check (for both users and providers) might be required to ensure long-term sustainability.

- If a basic level of service is being delivered and expenditure is outside the cost benchmarks, then there may be context-specific explanations; such as the service is in a densely-populated area with economies of scale, or, conversely, the area is difficult or remote to reach.

- Real expenditure on recurrent costs is a tiny fraction of these amounts.

Example of life cycle costs from Uganda

The Fontes Foundation studied the different costs over a period of seven years of three of their rural water projects in Uganda (Koestler, Koestler and Koestler, 2010). The three projects are situated in Katunguru Sub-County, part of Queen Elizabeth National Park in Rubirizi District in Western Uganda and the three communities Katunguru, Kazinga and Kisenyi have 730, 860 and 1040 inhabitants respectively. All three projects are managed through the community management model and are all small piped water schemes, with between 1 km and 2 km of pipes and one or two public taps. Since the ground water in the Rift Valley is salty, it is necessary to treat surface water.

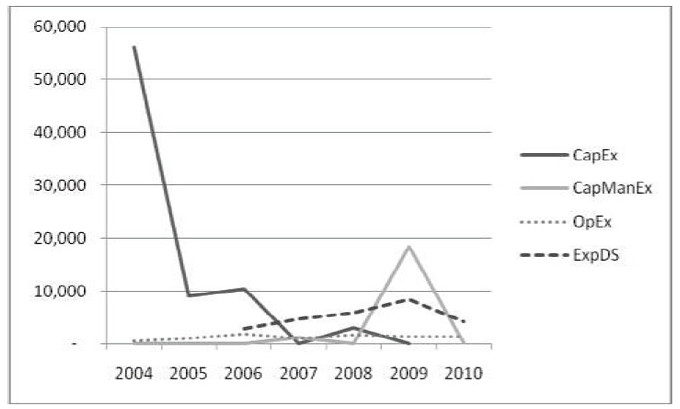

Figure 2 shows the total cash flow and the type of expenditure for one of the three projects; Katunguru. It shows that after the initial investment in 2004 (e.g. capital expenditure) a significant injection was necessary in 2009 to replace a broken generator. Unexpected increases in capital maintenance are usually accompanied by an increase in expenditure on direct support. Otherwise, the cash flow lies between 8,000 and 14,500 USD per year (Koestler, Koestler and Koestler, 2010).

Figure 2. Costs by categories for Katunguru water project in Uganda 2004-2010 in 2010 USD

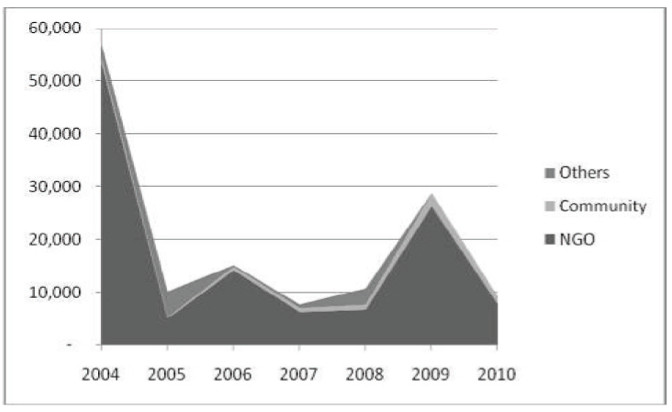

When the total cash flow is broken down into the life cycle cost categories, only a small amount of the total cash flow is needed per year, to keep the projects running, was covered by the community in form of operation and maintenance costs (e.g. 24%) as shown in figure 3, below (Koestler, Koestler and Koestler, 2010).

Figure 3. Total cash flow by source of income for Katunguru in 2010 USD

Key documents

- Fonseca, C. et al., 2010a. Life-cycle costs approach: glossary and cost components. (WASHCost briefing note; no. 1). The Hague, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- Fonseca, C. et al., 2010b. A multi dimensional framework for costing sustainable water and sanitation services in low-income settings: lessons from collecting actual life cycle costs for rural and peri-urban areas of Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mozambique and Andhra Pradesh. (WASHCost research report; V1.0). The Hague, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- IRC, 2012. Providing a basic level of water and sanitation services that last: cost benchmarks. (WASHCost infosheet; 1.) The Hague, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre

- Information sheet provides an overview of the minimum benchmarks for costing sustainable basic services in developing countries. The benchmarks have been derived from the WASHCost project dataset and the best available cost data from other organisations all over the world. The benchmarks are useful for planning, assessing sustainability from a cost perspective and for monitoring value for money.

- Koestler, L., Koestler, A.G. and Koestler, M.A., 2010. The cost of keeping a rural water system running: cost tracking of three rural water supplies in Uganda: paper presented at the IRC symposium ‘ Pumps, Pipes and Promises: Costs, Finances and Accountability for Sustainable WASH Services' in The Hague, The Netherlands from 16 - 18 November 2010. The Hague, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- Pezon, C., 2010. Decentralisation and the use of cost data in WASHCost project countries: synthesis of country reports 2009. (WASHCost briefing note; no. 2). [online] The Hague, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

Links

- WASHCost was a five-year action research programme, running from 2008 to 2012. The WASHCost team gathered information related to the costs of providing water, sanitation, and hygiene services for an entire life-cycle of a service - from implementation all the way to post-construction. The WASHCost programme was led by IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre with several partners to collect data in the rural and peri-urban areas of Burkina Faso, Ghana, India, and Mozambique. For more information see WASHCost.

- The Costing Sustainable Services online course was developed to assist governments, NGOs, donors and individuals to plan and budget for sustainable and equitable WASH services, using a life-cycle cost approach. The Life-cycle cost approach is a methodology for costing sustainable water, sanitation and hygiene service delivery and comparing the costs to the level of service received by users. For more information see: WASHCost Online Training.

- WASHCost data sets provide access to the validated life cycle cost and service level information collected in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Andhra Pradesh (India), and Mozambique between 2009 and 2010. The data has been collated from a number of sources, including infrastructure surveys, detailed household surveys and a range of specific research undertaken with stakeholders in each country. The data sets are available here.

- Triple-S (Sustainable Services at Scale) is a six-year, multi-country learning initiative to improve water supply to the rural poor. It is led by IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. The initiative is currently operating in Ghana and Uganda. Lessons learned from work in countries feeds up to the international level where Triple-S is promoting a re-appraisal of how development assistance to the rural water supply sector is designed and implemented. For more information see: Water Services That Last.