Operation and maintenance - Sustainable Sanitation

- The level of O&M is closely linked to ownership of a facility and the basic understanding of the technology and its functions.

- Every technology that is implemented in a sanitation system chain requires proper O&M to function.

- Different technologies at different steps in the sanitation chain need different people and different responsibilities for O&M.

- Clearly defined roles and accountabilities as well as appropriate support and training are essential for the management of O&M services.

- Institutional responsibilities as well as effective mechanisms for cost recovery are needed to ensure sustainable O&M.

Contents

1. Introduction

Reasons for non-functioning O&M services include lack of ownership or delegated responsibility for O&M, lack of skilled labour, high operating costs, excessive repair and replacement expenses. Additionally, the technical options chosen are not always the best suited to the local environment in which they shall be operated. Other reasons are closely related to the set-up of projects, which often focus only on construction of hardware instead of management components because hardware installations can be implemented faster and with fewer complications than management systems. Consultation with the local stakeholders and users regarding the most appropriate system for the local conditions often does not take place adequately. In most cases where the provision of sanitation services have failed, the root causes have been poor management, lack of planning, and failure to generate sufficient revenue to operate and maintain systems (Bräustetter, 2007).

2. What is O&M?

Operation refers to the daily activities of running and handling infrastructure (Sohail, 2001). In the sanitation context, operation additionally includes the planning, control and performance of the collection, treatment and disposal or reuse of the excreta or wastewater flows. Maintenance on the other hand involves the activities required to sustain existing assets in a serviceable condition (WHO, 2000) and includes three types:

- Preventive maintenance: Systematic routine actions needed to keep the installations and equipment in a condition that will ensure they can be operated satisfactorily, function efficiently and continuously, and last as long as possible at lowest cost.

- Corrective maintenance: This range of activities starts with minor repairs and replacements as dictated by the routine examinations up to corrections of serious damages and malfunctioning.

- Crisis maintenance: Maintenance which is undertaken only in response to breakdowns or public complaints.

3. Every technology needs O&M

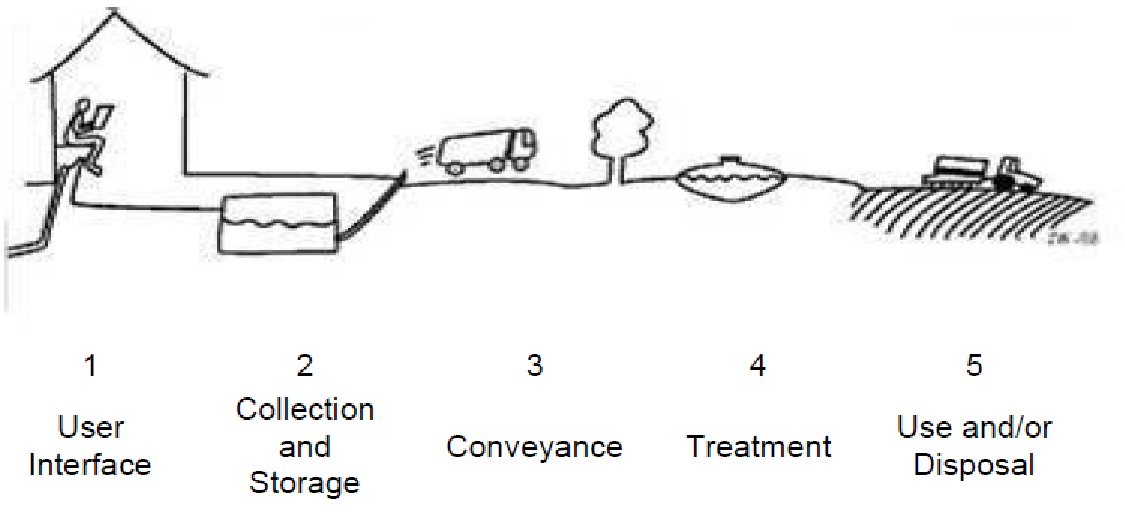

The responsibility for O&M of each functional item may be assigned to different stakeholders. For example, maintenance of the toilet (user interface) is often the responsibility of the household, while the treatment process is usually run by a municipal authority. Clear delineation of O&M tasks and responsibilities is critical for achieving a sustainable system.

The selection of technical designs and supporting institutional structures must always be matched to local conditions, both with respect to technical and socio-economic feasibility, and the management capacities and willingness of users and service providers (IRC, 1997).

4. Funding of O&M

Sustainable O&M requires planning and budgeting to carry out the necessary tasks. Decisions on who should fund sanitation O&M and how, receives far less attention than design and construction activities (Sohail, 2001).

Traditionally, municipalities and utilities are responsible for the O&M of centralized wastewater treatment systems but research in the 1990s in India and Thailand (IRC, 1997) has already pointed out that municipal budgets often fail to earmark funds for O&M of sanitation systems. Funding for day-to-day operation and basic maintenance (i.e. hiring a caretaker) can be sustainably sourced through revenue generating activities, as shown in the examples below. However, crisis maintenance and large scale repairs may require substantial funding beyond day-to-day turnover and can place high demands on limited budgets. Funds are not always readily available for this, in which case, microfinance institutions may be used to enable access to credit.

5. Responsibilities for O&M

For a well working sanitation system it is important to clarify and agree on roles and responsibilities already during the planning stage. During planning and design, division of responsibilities and definition of tasks and accountability require ample consideration and agreement between stakeholders. Creating conditions, in which responsibilities can be implemented as intended, may require awareness raising, motivation and incentives both for the agencies and the users (IRC, 1997). Furthermore, there are more stakeholders in the sanitation system beyond the municipality. Small scale providers, communities and households also play an important role in O&M. The choice of the management model is influenced by several framework conditions like capacity of community organizations, community skills, capacity of the private sector, etc. (Brikké, 2000).

In larger towns a town-wide management system may be installed for the overall coordination. In Vienna (Austria) for example, a municipal department is responsible for O&M of the sewer system while a holding company operates the central treatment plant through a mandate from the municipality. Decentralised systems on the other hand may have localised daily operations but should be monitored by higher level institutions. For example a school sanitation system may be managed by the school management but monitored by a national authority.

6. Development of service chains in practice

- The Kalungu Girls Secondary School (Uganda)

- Lessons learnt from the ROSA project funded by the EU (East Africa)

- The "Sanitation as a Business" program (Malawi)

- Institutional management of condominial sewers (Brazil)

- Public toilet served by a privatised water utility in Naivasha (Kenya)

- Sustainable sanitation in Kyrgyzstan (Central Asia)

7. Conclusion

The attention given to O&M of sanitation systems especially in developing and transition countries is usually little or no attention compared to the design and construction phases. The result of this is poor or non-functioning sanitation systems which pollute the environment and affect people’s health. This situation has been attributed to several reasons which includes among others: lack of ownership and skilled labour, high maintenance cost, and unsuitable technical options due to lack of consultation with the local stakeholders and users.

It is therefore important that O&M of sanitation systems is considered holistically during sanitation planning, designing, implementing and managing with clearly laid down tasks and responsibilities divided among the stakeholders along the whole sanitation chain. In doing this, it is equally important to allocate separate financial resources for routine O&M on sanitation systems. These financial resources must be explicitly determined from the planning stage and can be sustainably sourced through direct or indirect revenue generating activities.

8. Acknowledgements

SuSanA factsheet: Operation and maintenance of sustainable sanitation systems. April 2012. susana.org