Decentralisation

In order to increase sanitation and water management efficiency and improve equity and justice for local people, a participatory and community-based approach is crucial. Democratic decentralisation is a promising means of institutionalising and scaling up popular participation that makes sustainable sanitation and water management effective. Below focuses on the decentralisation process and its possible outcomes. In the full guide (link below), two case studies from South Africa and Bolivia highlight the diversity of decentralisation outcomes for sanitation and water management and the importance of a proper implementation process.

(Democratic) Decentralisation for Sustainable Sanitation and Water Management

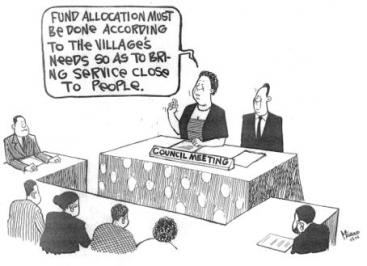

Decentralisation is any act in which a central government formally gives up powers to actors and institutions at lower levels, in a political-administrative and territorial hierarchy. Democratic (or political) decentralisation occurs when powers and resources are transferred to authorities representative of and downwardly accountable to local populations. The aim of democratic decentralisation is to increase popular participation in local decision-making and to increase accountability and efficiency of the government in the delivery of services. As local governments operate more closely with the people than any other level of government, they might be able to identify the needs and preferences of communities better than authorities in centralised governments.

Thus, decentralisation could be a logical first step to implement any sustainable sanitation and water management interventions on the local level. Only if resources and powers are decentralised, it is possible for local authorities to decide on the most sustainable solution in their local area. For ensuring the efficiency of the implementation tools, the participation of the local population should be starched, which is best possible with a democratic decentralisation reform. Public participation can in turn add to sustainable sanitation and water management.

The problem of service provision by local governments is that it may be hampered by the low capacity of local governments, corruption, elite capture and political influence. The lack of political accountability, people’s participation, transparency, policy coherence, capacity at the lower level and monitoring and evaluation have held back the success of decentralisation programmes in service delivery in water supply and sanitation in developing countries.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| - Helpful means to simplify implementation of many other SSWM tools - Local governments closer to civil society than central governments |

- Local governments often lack capacity and resources to take over responsibilities in a decentralisation process - Often, transfer of power is insufficient |

Main Benefits of Democratic Decentralisation

Decentralisation brings governments closer to the people. In order to increase sanitation and water management efficiency and improve equity and justice for local people, a participatory and community-based approach is crucial. “Democratic decentralisation is a promising means of institutionalising and scaling up popular participation that makes sustainable sanitation and water management effective.” (RIBOT 2002)

More precisely, decentralisation can lead to the following benefits:

Equity: Greater retention and fair or democratic distribution of benefits from local activities

Efficiency: Increased economic and managerial efficiency through:

- Accounting for costs in decision making: When communities and their representatives make decisions, they might take into account (“internalise”) the whole array of costs to local people.

- Increasing accountability: By bringing public decision making closer to the citizenry, decentralisation is believed to increase public-sector accountability and therefore effectiveness.

- Reducing transaction costs: Administrative and management transaction costs may be reduced by means that increase the proximity of local participants, and access to local skills, labour and local information.

- Matching services to needs: Bringing local knowledge and aspiration into project design, implementation, management and evaluation helps decision makers to better match actions to local needs.

- Mobilising local knowledge: Bringing government closer to people increases efficiency by helping to tap the knowledge, creativity and resources of local communities.

- Improving coordination: Decentralisation is believed to increase the effectiveness of coordination and flexibility among administrative agencies and in planning and implementation of development.

- Providing resources: Providing local communities with material and revenues can contribute to development.

How to Decentralise Government for Sanitation and Water Management

“Most current “decentralisation” reforms are characterised by insufficient transfer of powers to local institutions, under tight central-government oversight. Often, these institutions do not represent and are not accountable to local communities.” (RIBOT 2002)

These outcomes of decentralisation processes need to be avoided. Generally, it is difficult to decentralise governments for sustainable sanitation and water management without the support of the national (central) government. Some processes might be possible within a central government, others might not.

The following points should be considered within a decentralisation, especially when the central government focuses on decentralisation and supports the process:

- Central governments should work with local democratic institutions as a first priority. Governments, donors, and NGOs can foster local accountability by (a.) choosing to work with and build on elected local governments where they exist, (b.) insisting on and encouraging their creation elsewhere, (c.) encouraging electoral processes that admit independent candidates (since most do not), and (d.) applying multiple accountability measures to all institutions making public decisions.

- Sufficient and appropriate powers need to be transferred. Local and national governments, donors, NGOs, and the research community should work to develop sanitation and water management subsidiarity principles to guide the transfer of appropriate and sufficient powers to local authorities. Guidelines are also needed to assure an effective separation and balance of executive, legislative, and judiciary powers in the local arena.

- Support equity and justice. Central government interventions may be needed for reducing inequities and preventing elite capture of public decision-making processes. Central governments must also establish the enabling legal environment for organising, representation, rights, and resources so that local people can demand government responsibility, equity, and justice for themselves. Furthermore, the local governments need to set out clear policies and a legal framework within the national framework focusing sustainable sanitation and water management issues.

- Establish fair and accessible adjudication. Local governments should establish accessible independent courts, or access to national courts, channels of appeal outside of the government agencies involved in sanitation and water management, and local dispute resolution mechanisms. Donors and NGOs can also support alternative adjudication mechanisms to supplement official channels instead of replacing them.

- Support local civic education. People need to be informed of their rights. Laws should be written in clear and accessible language, and legal texts might be translated into local languages to encourage popular engagement and local government responsibility. When there are meaningful rights it is critical for people to know them. Local authorities need to be educated about their rights and responsibilities to foster responsible local governance.

- Give decentralisation time. Judge decentralisation only after it has been tried. Give it sufficient time to stabilise and bear fruit.

- Develop indicators for monitoring and evaluating decentralisation and its outcomes. By developing and monitoring indicators of progress in decentralisation legislation, implementation and outcomes can be evaluated and provide needed feedback that could keep decentralisation initiatives on track.

- Document the process.

- Find places for local government’s meetings. It is not enough that a local government exists and has power and resources, it needs a place to enable meetings, elections, etc.

- Inform the public. For a well working local government, the public needs to be informed about its actions and ideas. It is important to work transparent for the civil society.

- Avoid corruption. Corruption needs to be avoided in local governments. It is important for the local authorities to work transparent for the civil society and for higher governmental levels.

| To continue reading check out the complete guide, Decentralisation, on the SSWM website. |

Acknowledgements

- Doerte Peters, Decentralisation. Sustainable Sanitation and Water Management.