Conventional Gravity Sewer

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

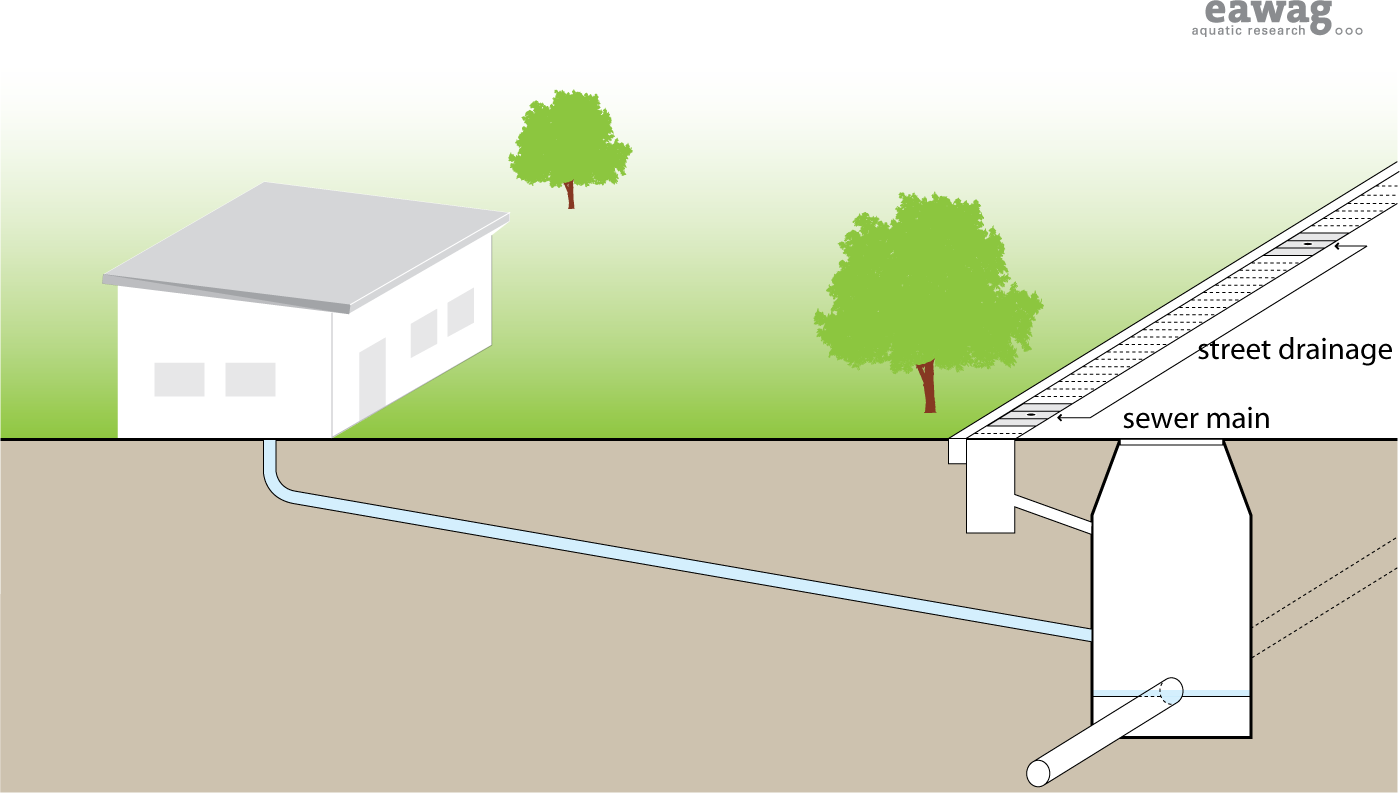

Conventional Gravity Sewers are large networks of underground pipes that convey blackwater, greywater and stormwater from individual households to a centralized treatment facility using gravity (and pumps where necessary).

The Conventional Gravity Sewer system is designed with many branches. Typically, the network is subdivided into primary (main sewer lines along main roads), secondary, and tertiary networks (network at the neighbourhood and household level).

Conventional Gravity Sewers do not require onsite pretreatment or storage of the wastewater. Because the waste is not treated before it is discharged, the sewer must be designed to maintain self-cleansing velocity (i.e. a flow that will not allow particles to accumulate). A self-cleansing velocity is generally 0.6–0.75m/s. A constant downhill gradient must be guaranteed along the length of the sewer to maintain self-cleaning flows. When a downhill grade cannot be maintained, a pump station must be installed. Primary sewers are laid beneath roads, and must be laid at depths of 1.5 to 3m to avoid damages caused by traffic loads.

Access manholes are placed at set intervals along the sewer, at pipe intersections and at changes in pipeline direction (vertically and horizontally). The primary network requires rigorous engineering design to ensure that a self-cleansing velocity is maintained, that manholes are placed as required and that the sewer line can support the traffic weight. As well, extensive construction is required to remove and replace the road above.

| Advantages | Disadvantages/limitations |

|---|---|

| - Stormwater and greywater can be managed at the same time. - Construction can provide short-term employment to local labourers. |

- A long time required to connect all homes. - Not all parts and materials may be available locally. - Difficult and costly to extend as a community changes and grows. - Requires expert design and construction supervision. - Effluent and sludge (from interceptors) requires secondary treatment and/or appropriate discharge. - High capital and moderate operation cost. |

Adequacy

Because they carry so much volume, Conventional Gravity sewers are only appropriate when there is a centralized treatment facility that is able to receive the wastewater (i.e. smaller, decentralized facilities could easily be overwhelmed).

Planning, construction, operation and maintenance require expert knowledge. Conventional Gravity Sewers are expensive to build and, because the installation of a sewer line is disruptive and requires extensive coordination between the authorities, construction companies and the property owners, a professional management system must be in place.

When stormwater is also carried by the sewer (called a Combined Sewer), sewer overflows are required. Sewer overflows are needed to avoid hydraulic surcharge of treatment plants during rain events. Infiltration into the sewer in areas where there is a high water table may compromise the performance of the Conventional Gravity Sewer.

Conventional Gravity Sewers can be constructed in cold climates as they are dug deep into the ground and the large and constant water flow resists freezing.

Health Aspects/Acceptance

This technology provides a high level of hygiene and comfort for the user at the point of use. However, because the waste is conveyed to an offsite location for treatment, the ultimate health and environmental impacts are determined by the treatment provided by the downstream facility.

Maintenance

Manholes are installed wherever there is a change of grade or alignment and are used for inspection and cleaning. Sewers can be dangerous and should only be maintained by professionals although, in well-organised communities, the maintenance of tertiary networks might be handed over to a well-trained group of community members.

References

- ASCE (1992). Gravity Sanitary Sewer Design and Construction, ASCE Manuals and Reports on Engineering Practice No. 60, WPCF MOP No. FD-5. American Society of Civil Engineers, New York. (A standard design text used in North America although local codes and standards should be assessed before choosing a design manual.)

- Tchobanoglous, G. (1981). Wastewater Engineering: Collection and Pumping of Wastewater. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Tchobanoglous, G., Burton, FL. and Stensel, HD. (2003). Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Reuse, 4th Edition. Metcalf & Eddy, New York.

Acknowledgements

The material on this page was adapted from:

Elizabeth Tilley, Lukas Ulrich, Christoph Lüthi, Philippe Reymond and Christian Zurbrügg (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies, published by Sandec, the Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries of Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

The 2nd edition publication is available in English. French and Spanish are yet to come.