Difference between revisions of "Expenditure Direct Support (ExpDS)"

(→Benchmarks expenditure direct support) |

(→Key documents) |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

* Whittington, D. et al., 2009. How well is the demand-driven, community management model for rural water supply systems doing? Evidence from Bolivia, Peru and Ghana. Water Policy 11(6), pp. 696–718. | * Whittington, D. et al., 2009. How well is the demand-driven, community management model for rural water supply systems doing? Evidence from Bolivia, Peru and Ghana. Water Policy 11(6), pp. 696–718. | ||

* Júlia Zita, Arjen Naafs, 2011. Cost of PEC-Zonal Activities in Mozambique, Analysis of contract costs from 2008 up to 2011, Briefing Note Moz. D 01. Available at < http://www.washcost.info/page/1804> [Accessed 21 December 2012] | * Júlia Zita, Arjen Naafs, 2011. Cost of PEC-Zonal Activities in Mozambique, Analysis of contract costs from 2008 up to 2011, Briefing Note Moz. D 01. Available at < http://www.washcost.info/page/1804> [Accessed 21 December 2012] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Links== | ==Links== | ||

Revision as of 06:06, 12 January 2013

Direct support is structured support to service providers and users or user groups related to the operation and management of a water, sanitation and hygiene services. Expenditure on direct support is the costs of providing such support. Direct support includes the following types of activities:

- performance monitoring

- technical advice and information

- administrative support (e.g. help with tariff setting)

- organisational support (e.g. to achieve legal status)

- conflict resolution

- identifying capital maintenance needs (including advice on financing)

- training and refresher courses.

The costs of support before and during the construction of a water or sanitation system are not included. They are considered to be capital expenditure software. Most community-based water service providers seek and receive some degree of direct support (Whittington et al., 2009), though often in an ad hoc manner, typically when they encounter a problem.

Direct support is often used synonymously with institutional support, post-construction support and follow-up support.

Difference between direct and indirect support

Direct support is always related to a particular project, programme or geographical area. Expenditure on indirect support is about creating and regulating the enabling environment for water, sanitation and hygiene services and is not particular to a programme or project.

Examples

Institutional arrangements for direct support

There are different institutional arrangements for the provision of direct support. Which model is most appropriate or cost-effective depends on the country context (Smits, 2012). Table 1 shows the main 5 types of arrangements.

Table 1. Institutional arrangements for direct support

| Direct support by local government | Local government is formally mandated to support external service providers and fulfills the support agent function internally, for example through local government technicians. |

| Local government subcontracting a specialised agency or individuals | Local governments contract an urban utility, a private company or an NGO to provide support. They may also contract individual entrepreneurs, such as handpump mechanics who provide a mix of direct support and operation and maintenance activities. |

| Central government of parastatal agencies | National government provides direct support from a national level, or via deconcentrated offices, or subcontracts a specialised agency to provide support. |

| Association of community-based service providers | Community-based service providers establish an association and then provide support to each other or hire a technician to support members of the association. |

| NGOs | In many cases, support provided by NGOs is ad hoc. Still there are a few examples where NOGs still have specific, direct support programmes. |

Source: Smits, 2012, 3

Benchmarks expenditure direct support

Based on research from the WASHCost project, the minimum expenditure on direct support to provide a basic level of water service (at 2011 prices) ranges from US$ 1 per person to just over US$ 3 per person (see table 2).

Table 2. Cost ranges for expenditure on direct support [min-max] in US$ 2011 per person, per year

| Borehole and handpump | 1-3 |

| All piped schemes | 1-3 |

Source: Fonseca and Burr, 2012

The costs as shown in table 2 (above) are based on the provision of a basic level of water service, as defined by WASHCost. A basic service implies that the following criteria have been realised by the majority of the population in the service area: People access a minimum of 20 litres per person per day, of acceptable quality (judged by user perception and country standards) from an improved source which functions at least 350 days a year without a serious breakdown, spending no more than 30 minutes per day per round trip (including waiting time).

The minimum expenditure on direct support required to provide a basic level of sanitation service ranges from US$ 0.5 to just over US$ 1.5 per person (2011 prices) (see table 3).

Table 3. Cost ranges for expenditure on direct support [min-max] in US$ 2011 per person, per year

| Traditional Pit latrine with an impermeable slab (often made from local materials) | 0.5 – 1.5 |

| Ventilated Pit latrine | 0.5 – 1.5 |

| Pour Flush or septic tank latrines | 0.5 – 1.5 |

Source: Fonseca and Burr, 2012

The costs as shown in table 3 (above) are based on the provision of a basic level of sanitation service, as defined by WASHCost. A basic sanitation service implies that all the following criteria have been realised by the majority of the population in the service area: At least some members of the household use a latrine with an impermeable slab at the house, in the compound or shared with neighbours. The latrine is clean even if it may require high user eff ort for pit emptying and other long term maintenance. The disposal of sludge is safe and the use of the latrine does not result in problematic environmental impact.

When using these benchmarks (see table 2 and 3) local factors must be taken into account. For example, the lower cost ranges were generally, but not always found in India, while cost data from Latin America tends to be higher than the maximum ranges, but usually relates to higher service levels.

For both water and sanitation:

- If expenditure is lower than the minimum range, then there is higher risk of reduced service levels or long-term failure. A reduced service level means that one or more service criteria (e.g. access, quantity, use, quality and reliability) are not achieved. Service criteria can vary according to country context and norms.

- In the WASHCost research, use of latrines and reliability of services tend to be lower when recurrent expenditure on things such as operation and maintenance is low.

- If expenditure is higher than the maximum range, an affordability check (for both users and providers) might be required to ensure long-term sustainability.

- If a basic level of service is being delivered and expenditure is outside the cost benchmarks, then there may be context-specific explanations; such as the service is in a densely-populated area with economies of scale, or, conversely, the area is difficult or remote to reach.

Expenditure on direct support in Mozambique between 2008 –2011

In 2008 a new approach for direct support aimed at supporting communities to improve their capacities to manage water supply and hygiene and sanitation conditions, called PEC zonal, was introduced in Mozambique in 18 districts. The PEC Zonal approach entails that a single (non-profit) organization or consultant is contracted by government to carry out all promotion of participation and education of the community in a district during a whole year (Zita and Naafs, 2011). The approach was scaled up country-wide in Mozambique from 2011.

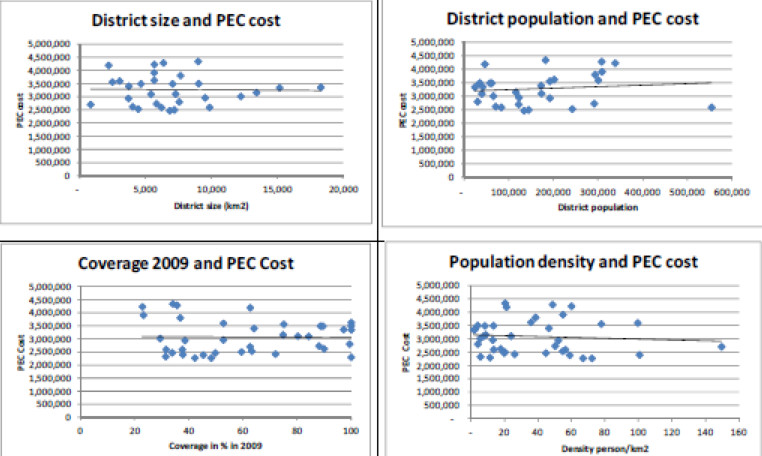

The WASHCost Mozambique project examined 94 PEC zonal contracts signed between 2008– 2011. Based on Zita and Naafs (2011, 1) the average cost of PEC zonal activities is 3,025,000 meticais (US$ 103,000) or 33 meticais (US$ 1.10) per person per year. No correlation was found between the cost of PEC zonal and variables such as district population, size of the district (km2), population density and water coverage in a district (see figure 2). The height of expenditure on direct support is therefore not directly related to these factors.

Key documents

- Kayser, G. et al., 2010. Assessing the Impact of Post-Construction Support—The Circuit Rider Model—on System Performance and Sustainability in Community-Managed Water Supply: Evidence from El Salvador. In: Smits, S. et al. (eds.), 2010. Proceedings of an international symposium. Kampala, 13-15 April 2010. The Hague: Thematic Group on Scaling Up Rural Water Services.

- Information sheet provides an overview of the minimum benchmarks for costing sustainable basic services in developing countries. The benchmarks have been derived from the WASHCost project dataset and the best available cost data from other organisations all over the world. The benchmarks are useful for planning, assessing sustainability from a cost perspective and for monitoring value for money.

WASHCost, (2012). Providing a basic level of water and sanitation services that last: cost benchmarks, information sheet 1. IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre Available at <http://www.washcost.info/page/2386> [accessed on 3 December 2012]

- Lockwood, H., 2002. Institutional Support Mechanisms for Community-managed Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Systems in Latin America. (Strategic Report 6) WA DC: EHP-Environmental Health Project of the USAID.

- Nyarko, K.B. et al., 2011. Post-construction costs of water point-systems. (Life-cycle costs in Ghana Briefing Note 2). Accra: WASHCost Ghana.

- This working paper analyses existing literature on primary cost data from seven countries of providing direct and indirect support to rural water service provision. It provides an overview of the features such support entails, how those features can be organised, what they cost and how they can be financed. It also provides recommendations to countries for strengthening support.

Smits S., Verhoeven J., Moriarty P., Fonseca F. and Lockwood H., 2011. Arrangements and cost of providing support to rural water service providers. WASHCost/Triple-S Working Paper 5. IRC, International Water and Sanitation Centre, November 2011. Available at < http://www.washcost.info/page/1567> [Accessed 21 December 2012]

- Smits, S., 2012. Direct support Post-Construction to Rural Water Service Providers. Triple-S Briefing note 6. IRC, International Water and Sanitation Centre, Available a< http://www.waterservicesthatlast.org/Resources/Building-blocks/Direct-support-to-service-providers> [Accessed 21 December 2012]

- RWSN, 2010. Myths of the Rural Water Supply Sector. St Gallen: Rural Water Supply Network.

- Whittington, D. et al., 2009. How well is the demand-driven, community management model for rural water supply systems doing? Evidence from Bolivia, Peru and Ghana. Water Policy 11(6), pp. 696–718.

- Júlia Zita, Arjen Naafs, 2011. Cost of PEC-Zonal Activities in Mozambique, Analysis of contract costs from 2008 up to 2011, Briefing Note Moz. D 01. Available at < http://www.washcost.info/page/1804> [Accessed 21 December 2012]

Links

- WASHCost was five-year action research programme, running from 2008 to 2012. The WASHCost team gathered information related to the costs of providing water, sanitation, and hygiene services for an entire life-cycle of a service - from implementation all the way to post-construction. The WASHCost programme was led by IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre with several partners to collect data in the rural and peri-urban areas of Burkina Faso, Ghana, India, and Mozambique. For more information see www.washcost.info

- The Costing Sustainable Services online course was developed to assist governments, NGOs, donors and individuals to plan and budget for sustainable and equitable WASH services, using a life-cycle cost approach. The Life-cycle cost approach is a methodology for costing sustainable water, sanitation and hygiene service delivery and comparing the costs to the level of service received by users. For more information see http://www.washcost.info/page/2448

- Triple-S (Sustainable Services at Scale) is a six-year, multi-country learning initiative to improve water supply to the rural poor. It is led by IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. The initiative is currently operating in Ghana and Uganda. Lessons learned from work in countries feeds up to the international level where Triple-S is promoting a re-appraisal of how development assistance to the rural water supply sector is designed and implemented. For more information see http://www.waterservicesthatlast.org/