Human-Powered Emptying and Transport

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Human-powered Emptying and Transport refers the different ways in which people can manually empty and/or transport sludge and septage.

Human-powered Emptying and Transport of pits and tanks refers to several things:

- using buckets and shovels;

- using a hand-pump specially designed for sludge (e.g. the Pooh Pump or the Gulper); and

- using a portable, manually operated pump (e.g. MAPET: Manual Pit Emptying Technology).

- using a pushcart or tricycle to transport containers and oil drums containing urine and excreta.

Contents

Pumps

Some sanitation technologies can only be emptied manually, for example, the Fossa Alterna or Dehydration Vaults. These technologies must be emptied with a shovel because the material is solid and cannot be removed with a vacuum or a pump. When sludge is viscous or watery it should be emptied with a hand-pump, a MAPET or a vacuum truck, and not with buckets because of the high risk of collapsing pits, toxic fumes, and exposure to the unsanitized sludge. The type of emptying that can, and should be employed, is very specific to the technology that needs emptying.

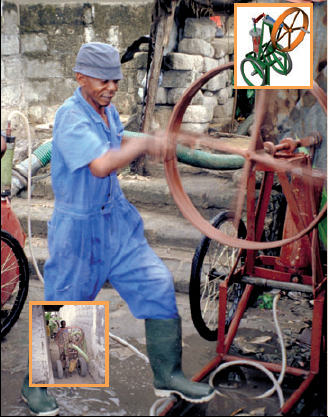

Manual sludge pumps like the Pooh Pump or the Gulper are relatively new inventions and have shown promise as being low-cost, effective solutions for sludge emptying where, because of access, safety or economics, other sludge emptying techniques are not possible. The pump works on the same concept as a water pump: the handle is pumped, the liquid (sludge) rises up through the bottom of the pump and is forced out of a tap (sludge spout). Hand-pumps can be made locally with steels rods and valves in a PVC casing. The bottom of the pipe is lowered down into the pit/tank while the operator remains at the surface to operate the pump, thus removing the need for someone to enter the pit. As the operator pushes and pulls the handle, the sludge is pumped up through the main shaft and is then discharged through the V-shaped discharge spout. The sludge that is discharged can be collected in barrels, bags or carts, and removed from the site with little mess or danger to the operator.

Gulper

One example of such a pump is The Gulper. This is a simple hand pump used to empty wet pit latrines and drain interceptor tanks. It consists of PVC pipes for the body, and stainless steel valves and puller rod. The Gulper is lowered into the pit with a footrest at groundlevel. The operator raises and lowers a puller rod, which pushes the sludge from the pit up through a pipe into a bucket or bag. Using the gulper, operators no longer need to climb into the pits and come in contact with the septic sludge. It is also much less time consuming as it removes around 3 litres of sludge per stroke. It is a cheaper method of improving sanitation, than trying to replace the pits by proper latrines. For more information about the Gulper see http://www.ideas-at-work.org/pdf/Gulper_pit_emptying_device.pdf

MAPET

A MAPET consists of a hand pump connected to a vacuum tank of 200 litre mounted on a pushcart. A hose is connected to the tank and is used to suck sludge from a pit. When the hand pump is turned, air is sucked out of the vacuum tank and sludge is sucked up into the tank. Depending on the consistency of the sludge, the MAPET can pump up to a height of 3m. Sludge is transported to a neighbourhood collection / disposal point from where vacuum tankers transfer it to city treatment plants.

A motorized version of the MAPET is the Vacutug, developed by UN-Habitat.

Cartage systems

Tricycles and push carts can be used to transport containers and oil drums containing urine or excreta. Push carts and tricycles (pedal or motorised) can access small streets. Tricycles can speed up the collection operation and increase the radius of the collection in urban areas, transporting the containers to transfer stations or to community treatment facilities. From transfer stations, urine and excreta can be loaded onto trucks or tractors, which can haul a larger volume over a long distance. Tricycles can collect door to door, although urine can also be collected in larger containers serving a number of houses.

| Advantages | Disadvantages/limitations |

|---|---|

| - Potential for local job and income generation. - Can access small streets - Not dependent on large, cost-intensive infrastructure. - Gulper can be built and repaired with locally available materials. - Low to moderate capital; variable operating costs depending on discharge point (sludge transport over 0.5km is impractical). - Provides service to unsewered areas/communities. - Easy to clean and reusable. |

- Spills may happen. - Time consuming: can take several hours/days depending on the size of the pit. - MAPET requires some specialized repair (welding). -Highly depending on willingness to pay for regular removal of excreta. - Cartage systems are only appropriate for small haul distances and small volumes. |

Adequacy

Hand-pumps are appropriate for areas that are either not served by vacuum trucks, where vacuumtruck emptying is too costly, or where narrow streets and poor roads may limit the ability of a vacuum truck to access the site. The hand-pump is a significant improvement over the bucket method and could prove to be a sustainable business opportunity in some regions. The MAPET is also well suited to dense, urban and informal settlements, although in both cases, the distance to a suitable sludge discharge point is a limiting factor. These technologies are more feasible when there is a Transfer Station or Sewer Discharge Station nearby.

One government-run emptying programme implemented a manual emptying scheme with great success by providing employment to community members with adequate protection and an appropriate wage.

Pushcarts and tricycles are especially appropriate in flat urban areas, with access roads. Pushcarts and tricycles are not appropriate for collecting large volumes (> 300 litre, > 300 kg) or for longer distances.

Health Aspects/Acceptance

Depending on cultural factors and political support, manual emptiers may be viewed as providing an important service to the community. Government-run programmes should strive to legitimize the work of the labourer and help improve the social climate by providing permits, licences and helping to legalize of the practice of manually emptying latrines. The most important aspect of manual emptying is ensuring that workers are adequately protected with gloves, boots, overalls and facemasks. Regular medical exams and vaccinations should be required for everyone working with sludge.

Upgrading

To save time, vacuum trucks can be used rather than manual labour if it is appropriate and/or available.

Maintenance

The MAPET and Sludge Pumps require daily maintenance (cleaning, repairing and desinfection). Workers that manually empty latrines should clean and maintain their protective clothing and tools to prevent contact with the sludge. If manual access to the contents of a pit require breaking open the slab, it may be more cost effective to use a Gulper to empty the latrine. The Gulper cannot empty the entire pit and therefore, emptying may be required more frequently (once a year), however, this may be a cheaper alternative than replacing a broken slab.

Acknowledgements

The material on this page was adapted from:

Elizabeth Tilley, Lukas Ulrich, Christoph Lüthi, Philippe Reymond and Christian Zurbrügg (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies, published by Sandec, the Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries of Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

The 2nd edition publication is available in English. French and Spanish are yet to come.

References and external links

- Eales, K. (2005). Bringing pit emptying out of the darkness: A comparison of approaches in Durban, South Africa, and Kibera, Kenya. Building partnerships for Development in Water and Sanitation, UK. Available: http://www.bpd-waterandsanitation.org (A comparison of two manual emptying projects.)

- Ideas at Work (2007). The ‘Gulper’ – a manual latrine/drain pit pump. Ideas at Work, Cambodia. Available: http://www.ideas-at-work.org

- Muller, M. and Rijnsburger, J. (1994). MAPET. Manual Pit-latrine Emptying Technology Project. Development and pilot implementation of a neighbourhood based pit emptying service with locally manufactured handpump equipment in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 1988–1992. WASTE Consultants, Netherlands.

- Oxfam (n.d.). Manual Desludging Hand Pump (MDHP) Resources. Oxfam, UK. Available: http://desludging.org

- Pickford, J. and Shaw, R. (1997). Emptying latrine pits, Waterlines, 16(2): 15–18. (Technical Brief, No. 54). Available: http://www.lboro.ac.uk

- Sugden, S. (n.d.). Excreta Management in Unplanned Areas. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK. Available: http://siteresources.worldbank.org