Solar powered pumps

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photo: Bob Freling's Solar Blog.

The climate in many countries in the developing world is suitable for solar pumping. Solar energy is a valid option for small-scale water pumping in rural areas where the demand is regular, such as for drinking water, but it may also be used for irrigation. Applications of solar systems are growing at steady rate.

Photovoltaics (PV) is a technology that converts sunlight directly into electricity. It was discovered in 1839 by the French scientist Antoine Henri Becquerel. About 50 years ago, the space programmes provided an incentive for the development of crystalline silicon solar cells. The production of PV modules began.

With the global drive to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, PV technology is increasingly used as a mainstream form of electricity generation. Many thousands of systems are presently in use and the vast potential for PV as an energy source has not yet been utilized.

PV modules provide an independent, reliable electrical power source at the point of use, making them particularly suited to remote locations. PV systems are technically viable and with more commercial applications the technology is developing fast and prices are coming down, making PV more and more economically feasible for rural water supplies.

Contents

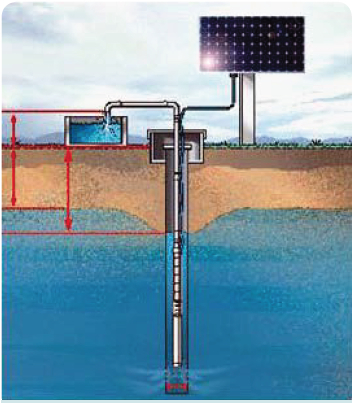

Suitable conditions

With solar water systems the water is pumped during the peak sunshine hours of the day. It can be stored in a tank, and therefore it is not necessary to use batteries. The storage tank can be sized to provide some reserve during cloudy or rainy days. In sub-Saharan Africa the typical storage is about 3 to 5 days of water demand. In environments where rainy seasons occur, rainwater harvesting can offset the reduced output of the solar pump during this period.

To properly size the size of solar panel(s) needed, refer to WASH Technology Information Packages, pages 130 & 131. Before that are great maps showing solar ranges and intensities in different regions of the world.

Construction, operations and maintenance

Solar panels are a very reliable piece of equipment and many manufacturers sell the panels with a guarantee of 25 years. It should be noted that such a warranty can only be honoured if the supplier is still in business in 25 years. Therefore, it is advisable to select reliable suppliers rather than to choose the cheapest source.

Solar PV modules are normally specified by Watt-peak. Wattpeak or Wp is the measure of power output of photovoltaic solar energy. They are very costly pieces of equipment. A 50 Wp module costs several hundred dollars and has a good resale value in many countries. Theft is already a problem in some areas.

There are three main types of cells on the market: monocrystalline silicon, multi-crystalline silicon, and amorphous silicon. New, non-silicon types such as cadmium telluride (CdTe) and copper indium disellenide (CIS) have recently become available.

Maintenance

Dust must be removed from the glass plates of the module regularly. In addition, external wires, the supporting structure of the array, covers for the electronic components, and a fence may need occasional repairs. Wood or metal parts that are sensitive to corrosion must be painted every year. Much of the additional electrical and electronic equipment should function automatically for at least 10–15 years, although batteries, AC/DC converters, engines and pumps may need more frequent servicing.

Local organization can be very simple, consisting mainly of appointing a caretaker and collecting fees. However, an adequate number of technicians for repairing such systems must be available at regional or national level.

Expected life cycle: Eighteen years or more for modules.

Security aspects

Theft and vandalism of solar photovoltaic modules poses perhaps the greatest threat to solar PV systems. To reduce this risk, it is imperative for the community to be fully involved in any PV installation project and to have complete ownership upon completion. This ownership should include the responsibility for maintenance, operation and replacement costs of damaged or stolen components.

Theft prevention normally includes fencing. For fences to be effective they should be 2 metres high, with barbed wire, and have gates with proper locks. Communities may also decide to employ a night guard and allocate money from their budget for security staff salaries.

Costs

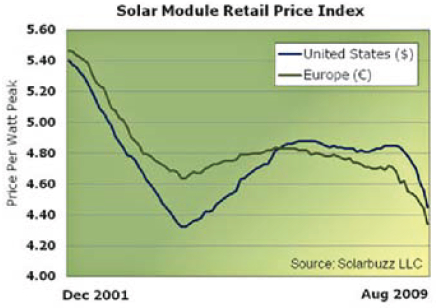

The prices of PV modules have fluctuated a lot over the last decade, but in 2009 there was a sharp fall in prices. These developments are influenced by raw material prices and the market situation. Below, the chart shows the changes in price from 2001 to 2009. It is advisable to check for up-to-date price information at solarbuzz.com.

Cost savings

Examples from the field show that the high initial costs of PV solar pumping systems can be recouped over a five-year period, due to savings on fuel. Since it is unlikely that fuel costs will decrease (and it is likely that capital costs of solar arrays will go down), the period should be even shorter in the future, making solar pumping an increasingly viable option.

Field experiences

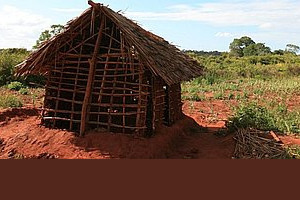

For the first time, women farmers in the rural villages of Bessassi and Dunkassa, in northern Benin, are able to grow vegetables and fruits during the six month dry season, improving food security and nutrition for themselves and their families. Farmers are also increasing their income by selling excess crops in the market. Now entering its third year, SELF's Solar Market Garden project has proved that solar energy can provide long term solutions to hunger, malnutrition and poverty in developing nations.

In addition, since December 2010, the villagers of Bessassi and Dunkassa now have access to clean drinking water via water wells powered by custom arrays of solar-panels ranging from 1.2 - 4 kW. This particular combination is not only a long-term solution, but can also be replicated all over the African continent.

Akvo RSR Projects

MWA-LAP: Colombia |

Water, Food & Sanitation for School + Community |

Manuals, videos and links

- Food Security: Using Solar Power to Transform Rural Agriculture in Benin's Kalalé District. Bob Freling's Solar Blog.

- [1] Details of the prototype 150W solar powered rope pump estimated to cost $600

Acknowledgements

- WASH Technology Information Packages – for UNICEF WASH Programme and Supply Personnel. UNICEF, 2010.

- Brikke, François, and Bredero, Maarten. Linking technology choice with operation and maintenance in the context of community water supply and sanitation: A reference document for planners and project staff. World Health Organization and IRC Water and Sanitation Centre. Geneva, Switzerland 2003.