Integrating Gender Perspective in Sustainable Sanitation

Key messages from this factsheet are:

- Gender equality is an integral part of sustainable sanitation meaning that the sanitation system should consider the differing needs and should be suitable for women, men and children.

- Women are often involved in water, hygiene and sanitation but lack support to deal with these issues

- Planning, design and implementation of a sanitation programmes should not be regarded only as a male domain but can and should be equally undertaken by women.

- There is a widespread lack of suitable sanitation facilities compounded by a lack of privacy. This increases female vulnerability to violence and impacts their health, wellbeing and dignity.

- Data regarding gender needs should be disaggregated to give recognition and acknowledgment to women’s needs and priorities.

- There is an unspoken but grave situation in the everyday lives of millions of school girls and women that make it difficult for them to walk freely and in a comfortable manner, to go to the toilet or to manage their menstruation sustainably.

- The special needs of menstruating girls and women need to be considered in appropriate sanitation programme designs by providing adequate female hygiene materials, discreet disposal and washing facilities.

Contents

1. Background on gender and sanitation

Access to safe and sustainable sanitation is essential to ensuring health and wellbeing. It reduces the burden of treating preventable illnesses and is a prerequisite for ensuring education for all and the promotion of economic growth in the poorest parts of the world. Access to adequate sanitation is a matter of security, privacy and human dignity. Integrating a gender perspective into the sanitation sector does not only require addressing differences in gender relations, it also means uncovering and challenging uneven hierarchical structures based on gender. Consequently, a gender-sensitive approach seeks to equalise the uneven distribution of sanitation roles and responsibilities and the access to safe and appropriate facilities by considering the basic needs of all men, women and children. One of the most significant divides between women and men, especially in developing countries, is found in the sanitation and hygiene sector. The provision of water, hygiene and sanitation is often considered a woman’s task. Women are promoters, educators and leaders of home and community-based sanitation practices yet their own concerns are rarely addressed. Societal barriers often restrict their involvement in decisions regarding sanitation facilities and programmes (GWA, 2006).

In many societies, women’s views, in contrast to those of men, continue to be systematically under-represented in decision-making bodies (ADB, 1998). This lack of a participatory approach is closely related to the uneven power structures in decision-making processes that characterise these societies and the sanitation sector in particular. Where sincere efforts have been made to integrate gender perspectives into the water and sanitation sector, these have unfortunately often failed to address strategic gender needs (Coles and Wallace, 2005).Women suffer more than men when there is a lack of appropriate sanitation facilities. Women suffer more indignity from defecating and urinating in the open than men and in some countries are regularly at risk of assault and rape while going to the toilet (COHRE et al., 2008). In many countries, hygiene conditions in public toilets are poor and spread infectious diseases. In the absence of sanitary facilities or due to cultural reasons, women in many countries often have to wait until dark to go to the toilet or the bush. As a result, these women try to drink as little as possible during the day and often suffer from associated health problems such as urinary tract infections, chronic constipation and other gastric disorders (GWA, 2006; Milhailova and Diaz, 2007).

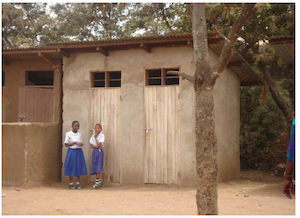

In rural areas, men avoid the stench of unimproved pit latrines and relieve themselves outside whilst women remain dependent on the pit latrines. Often in urban areas, women and girls face innumerable security risks and other dangers when they use public facilities which are open to both men and women. Research in East Africa indicates that safety and privacy are women’s main concerns when it comes to sanitation facilities (Hannan and Andersson, 2002). Without safe sanitation, women’s dignity, safety and health are at stake.

2. What does gender mean?

Gender identifies the social relationships between women and men. Gender is socially constructed; gender relations are contextually specific and often change in response to altering circumstances (Moser, 1993). Men and women fulfil a number of concurrent social roles and social relations that are influenced by other people. Race, ethnicity, age, culture, tradition, religion and an “individual’s position” (wealth, status) also contribute to differentiating the experience of being a man or a woman within a particular society. Gender identity and gender roles are the result of learned behaviour and given the right impetus and motivation can change. The challenge in this context is that men’s and women’s gender roles determine their access to - as well as their power and control over - adequate water supply, sanitation facilities and hygiene. Unchallenged, these roles can continue to have a direct negative effect on communities, households and individuals, in particular women and children.

Gender equality (or equity) means equal visibility, opportunities and participation of women and men in all spheres of public and private life. Gender equity is often guided by a vision of human rights that incorporates acceptance of the equal and inalienable rights of women and men. Gender equality is not only crucial for the wellbeing and development of individuals but also for the evolution of societies and the development of countries. However, gender equality has not yet been achieved.

3. International commitments and goals for gender equality in relation to sanitation

Millennium Development Goal (MDG 3) calls for the promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment. Four indicators are used to monitor progress: education, literacy, wage employment and political representation.

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (1979) is the most important legally-binding international instrument for the protection of women’s rights. Addressing the living conditions of women in rural areas, the CEDAW states in article 14(2) (h), that parties shall ensure that women have “the right to enjoy adequate living conditions, particularly in relation to housing, sanitation, electricity and water supply, transport and communication.”

The UN Resolution of the 23rd Special Session of the General Assembly, New York in June 2000 emphasised “Further actions and initiatives to implement the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action”. Actions should be taken by governments at the national level to: “Ensure universal and equal access for women and men throughout the lifecycle to social services related to health care, including education, clean water and safe sanitation, nutrition, food security and health education”.

Human rights: In July 2010, the UN General Assembly recognised for the first time that access to water and sanitation is a basic human right. This right was confirmed in a resolution by the Human Rights Council in October 2010 and was declared legally binding.

4. The role of women an men in sanitation

In most countries, cleaning toilets is primarily the responsibility of women, for any type of sanitation system. Men are generally responsible for the construction and technical maintenance of the sanitation facility (e.g. digging and repairing). In many households, women are responsible for making sure there is sufficient water for sanitation purposes which may involve carrying water for long distances. They are also involved in pit emptying activities; although this is a burden for men as well (anecdotal evidence suggests that e.g. in India and Pakistan, more women than men have to empty pits whereas in countries in Sub-Saharan Africa it is the other way around). Either way, the conditions under which such manual pit emptying is carried out are usually appalling, regardless of whether it is men or women doing the work.

In the design, location, selection and construction of sanitation facilities, too little attention is paid to the specific needs of women and men, girls and boys as well as their respective roles in terms of maintaining the facilities. Sanitation programmes, like many other development programmes, often assume a high degree of gender neutrality. This results in gender-specific failures such as toilets with doors facing the street in which women feel insecure, school urinals that are too high for boys, a lack of disposal facilities for female sanitary materials and pourflush toilets that increase the workload of those women who have to carry the water needed for the toilets.5. Methods to assess the role and impact on females in sanitation

This lack of progress is partly due to the general absence of specifically collected data from and about females in water and sanitation. This lack of data causes issues such as:

- Difficulties to adequately measure change over time, and the impact interventions have had on gender equality and whether such changes contribute towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) or other goals.

- Difficulties to make effective analytical assessments of the comparative situation of women and men.

- Sound policy formulation is hampered by the lack of information about the gender-related realities of water and sanitation access as well as the need and use of sanitation in private and public sectors. Genderdisaggregated data is crucial when assessing the effects of policy measures on women and men.

6. Special needs of girls and women during menstruation

- Well-designed, clean, safe, private toilets in sufficient numbers for female students with locks on the inside of the doors

- Clean water inside or very near to the toilets so girls can wash menstrual blood off their hands and stains from their clothing without boys watching;

- Adequate and culturally appropriate disposal systems for used menstrual materials, including dustbins inside latrines and an incinerator or pit where materials can be burnt;

- A private location for girls who use menstrual cloths so these can be washed and dried;

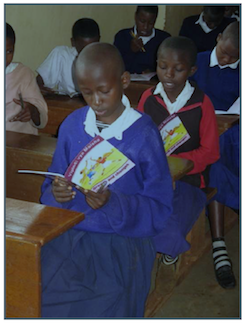

- Availability of credible and empowering puberty and menstrual management guidance, such as the girl’s puberty book “Growth and changes” developed through participatory activities with girls in Tanzania (Sommer, 2009) or the guide to menstrual management for school girls “Growing up at school” developed in Zimbabwe (Kanyemba, 2011);

- Sensitising school administrators and teachers to challenges associated with menstrual hygiene management;

- The provision of menstrual adaptable underwear for girls (with removable sanitary pads).

7. Integrating gender in sanitation

According to the Ecosoc (UN Economic and Social Council) definition, gender mainstreaming can be understood as “the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in any area and at all levels. The following elements of the gender mainstreaming process can safeguard a gender perspective in sustainable sanitation (ADB, 1998).

- Gender analysis

- Impact assessment

- Composition of project teams

- Empowerment

- Financing and budget allocations

- Income generation

- Involvement of boys and men

8. Acknowledgements

SuSanA factsheet: Capacity development for sustainable sanitation. April 2012. susana.org