Co-composting

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

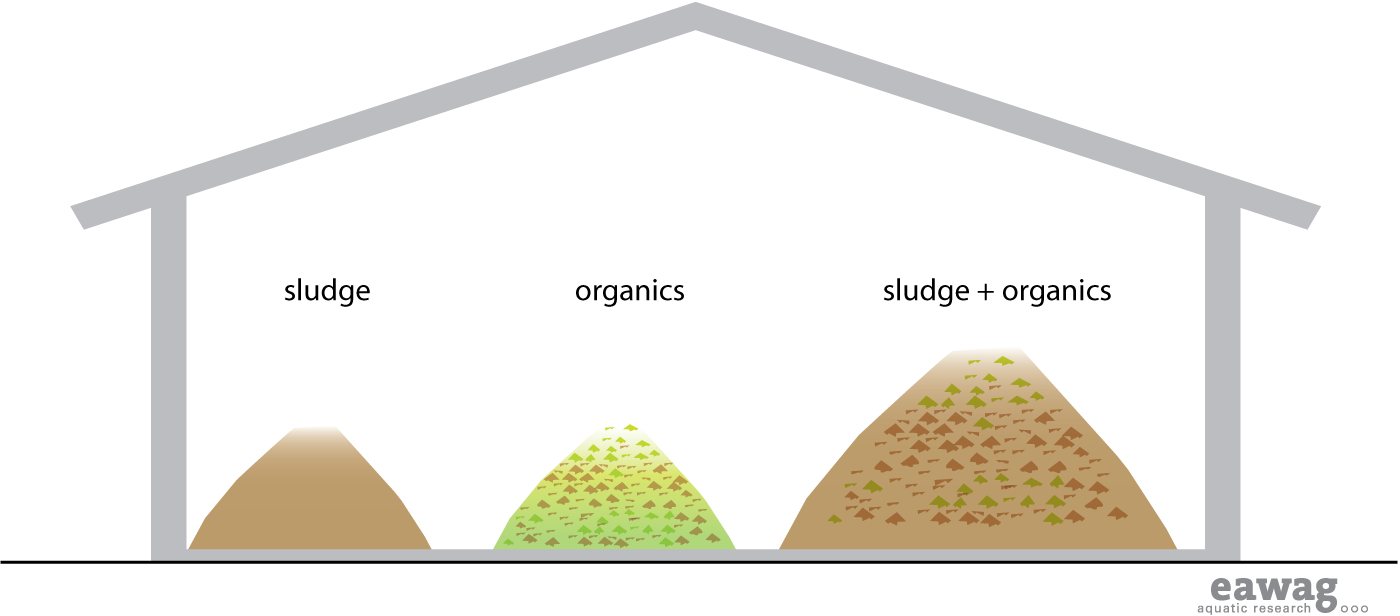

Co-Composting is the controlled aerobic degradation of organics using more than one materials (Faecal sludge and Organic solid waste). Faecal sludge has a high moisture and nitrogen content while biodegradable solid waste is high in organic carbon and has good bulking properties (i.e. it allows air to flow and circulate). By combining the two, the benefits of each can be used to optimize the process and the product. For dewatered sludges, a ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 of dewatered sludge to solid waste should be used. Liquid sludges should be used at a ratio of 1:5 to 1:10 of liquid sludge to solid waste.

Open co-composting

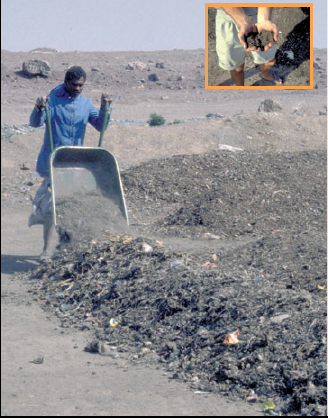

There are two types of Co-Composting designs: open and in-vessel. In open composting, the mixed material (sludge and solid waste) is piled into long heaps called windrows and left to decompose. Windrow piles are turned periodically to provide oxygen and ensure that all parts of the pile are subjected to the same heat treatment. Windrow piles should be at least 1m high, and should be insulated with compost or soil to promote an even distribution of heat inside the pile. Depending on the climate and available space, the facility may be covered to prevent excess evaporation and protection from rain.

To adequately treat excreta together with other organic materials in windrows, the WHO (1989) recommends active windrow co-composting with other organic materials for one month at 55-60°C, followed by two to four months curing to stabilise the compost. This achieves an acceptable level of pathogen kill for targeted health values.

In-vessel co-composting

In-vessel composting requires controlled moisture and air supply, as well as mechanical mixing. Therefore, it is not generally appropriate for decentralized facilities. Although the composting process seems like a simple, passive technology, a well-working facility requires careful planning and design to avoid failure.

| Advantages | Disadvantages/limitations |

|---|---|

| - Through co-composting, a useful and safe end product is generated that combines nutrients and organic material. - Easy to set up and maintain with appropriate training - Provides a valuable resource that can improve local agriculture and food production - High removal of helminth eggs possible (< 1 egg viable egg/g TS) - Can be built and repaired with locally available materials - Toilet paper is decomposed - Low capital cost; low operating cost - Potential for local job creation and income generation - No electrical energy required |

- Long storage times - Requires expert design and operation - limited control of vectors and pest attraction - Labour intensive - Lower cost variants requires a large land area (which is well located) |

Contents

Adequacy

A Co-Composting facility is only appropriate when there is an available source of well-sorted biodegradable solid waste. Mixed solid waste with plastics and garbage must first be sorted. When done carefully, Co-Composting can produce a clean, pleasant, beneficial product that is safe to touch and work with. It is a good way to reduce the pathogen load in sludge.

Depending on the climate (rainfall, temperature and wind) the Co-Composting facility can be built to accommodate the conditions. Since moisture plays an important role in the composting process, covered facilities are especially recommended where there is heavy rainfall. The facility should be located close to the sources of organic waste and faecal sludge (to minimize transport) but to minimize nuisances, it should not be too close to homes and businesses. A well-trained staff is necessary for the operation and maintenance of the facility.

Adding excreta, especially urine, to household organics produces compost with a higher nutrient value (N-P-K) than compost produced only from kitchen and garden wastes. Co-composting integrates excreta and solid waste management, optimizing efficiency.

Health Aspects/Acceptance

Although the finished compost can be safely handled, care should be taken when handling the faecal sludge. Workers should wear protective clothing and appropriate respiratory equipment if the material is found to be dusty.

Upgrading

Robust grinders for shredding large pieces of solid waste (i.e. small branches and coconut shells) and pile turners help to optimize the process, reduce manual labour, and ensure a more homogenous end product.

Maintenance

The mixture must be carefully designed so that it has the proper C:N ratio, moisture and oxygen content. If facilities exist, it would be useful to monitor helminth egg inactivation as a proxy measure of sterilization. Maintenance staff must carefully monitor the quality of the input materials, keep track of the inflows, outflows, turning schedules, and maturing times to ensure a high quality product. Manual turning must be done periodically with either a front-end loader or by hand. Forced aeration systems must be carefully controlled and monitored.

Acknowledgements

The material on this page was adapted from:

Elizabeth Tilley, Lukas Ulrich, Christoph Lüthi, Philippe Reymond and Christian Zurbrügg (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies, published by Sandec, the Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries of Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

The 2nd edition publication is available in English. French and Spanish are yet to come.

References and external links

- Cofie, O., et al. (2006). Solid–liquid separation of faecal Sludge using drying beds in Ghana: Implications for nutrient recycling in urban agriculture. Water Research 40(1): 75–82.

- Koné, D., et al. (2007). Helminth eggs inactivation efficiency by faecal Sludge dewatering and co-composting in tropical climates. Water Research 41(19): 4397–4402.

- Obeng, LA. and Wright, FW. (1987). Integrated Resource Recover. The Co-Composting of Domestic Sold and Human Wastes. The World Bank + UNDP, Washington.

- Shuval, HI., et al. (1981). Appropriate Technology for Water Supply and Sanitation; Night-soil Composting. UNDP/WB Contribution to the IDWSSD. The World Bank, Washington. The following reports can all be found in the Faecal Sludge Co-Composting section of the Sandec Website: www.sandec.ch

- Montangero, A., et al. (2002). Co-composting of Faecal Sludge and Soil Waste. Sandec/IWMI, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

- Strauss, M., et al. (2003). Co-composting of Faecal Sludge and Municipal Organic Waste- A Literature and State-of- Knowledge Review. Sandec/IMWI, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

- Drescher. S., Zurbrügg, C., Enayetullah, I. and Singha, MAD. (2006). Decentralised Composting for Cities of Low- and Middle-Income Countries - A User’s Manual. Eawag/Sandec and Waste Concern, Dhaka.