Nutrition Sensitive Value Chains

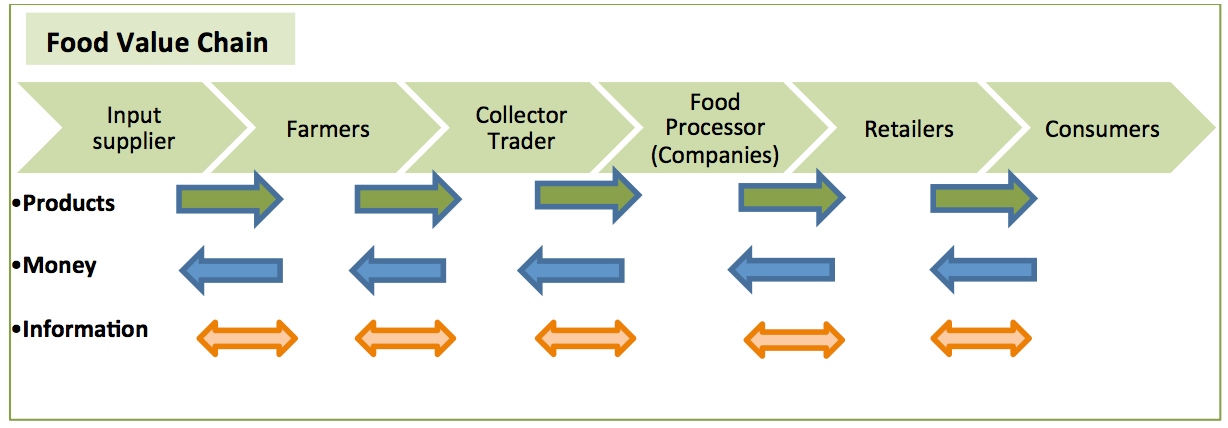

A food value chain is: the full range of farms and firms and their successive coordinated value-adding activities that produce particular raw agricultural materials and transform them into particular food products that are sold to final consumers and disposed of after use (FAO, 2000). The functioning of food value chains is essential for the availability and accessibility of good quality and nutritious food, which is a prerequisite for nutrition sensitive interventions to succeed.

Nutrition sensitive refers to addressing the underlying determinants of nutrition. According to the World Bank, these underlying determinants include adequate access to food, healthy environments, adequate health services and care practices. In their turn these are determined by the distribution of wealth and resources, which can be extremely unequal. As a result it might happen that those who work the land and produce the food experience hunger and discrimination.

Nutrition sensitive interventions involve multiple sectors (agriculture, health, social protection, education, water supply plus sanitation) and include clear nutrition objectives. In particular, objectives that enable communities to achieve food and nutrition security. In several of the definitions of nutrition sensitive development, it is stressed that it will only contribute to improved nutrition when these objectives are included and supported by (national) government policies. Only governments can directly influence relevant areas for legislation. In addition, governments could pro-actively implement and/or support programs that directly contribute to nutrition improvement among target groups.

In the case of nutrition sensitive value chains, crucial elements are women's empowerment and awareness raising on nutrition, explaining the importance of healthy food throughout the lifecycle. For more details refer to Nutrition Education - Design. A practical toolkit on how to integrate a gender perspective in agricultural value chains, can be found here: AgriProFocus.

| The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) suggests the following set of 9 principles for the development of Nutrition-sensitive/enhanced value-chains, taking into account the benefits of applying value-chain concepts, as well as the very real limitations.

1. Start with explicit outcome oriented nutritional goals. For example: increase the supply of nutritious foods that is accessible to the poor all year round.

5. Focus on the functioning and coordination of the whole chain in order to create sustainable solutions. For example: interventions at several points along the chain to enhance coordination of the whole chain, or a small number of actions to fix the problem and create incentives for changes to be made elsewhere in the chain. Form alliances between different actors involved, although this might bring challenges. |

Acknowledgements

- C. Hawkes and M. T. Ruel. Value Chains for Nutrition, 2020 Conference paper 4, IFPRI, 2011.

- WUR, Knowledge Co-creating Portal Nutrition Security, Nutrition Sensitive Value Chains.

- Agri-ProFocus Learning Network.