Single Pit

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Single Pit is one of the most widely used sanitation technologies. Excreta, along with anal cleansing materials (water or solids) are deposited into a pit. Lining the pit prevents it from collapsing and provides support to the superstructure.

As the Single Pit fills, two processes limit the rate of accumulation: leaching and degradation. Urine and anal cleansing water percolate into the soil through the bottom of the pit and wall while microbial action degrades part of the organic fraction.

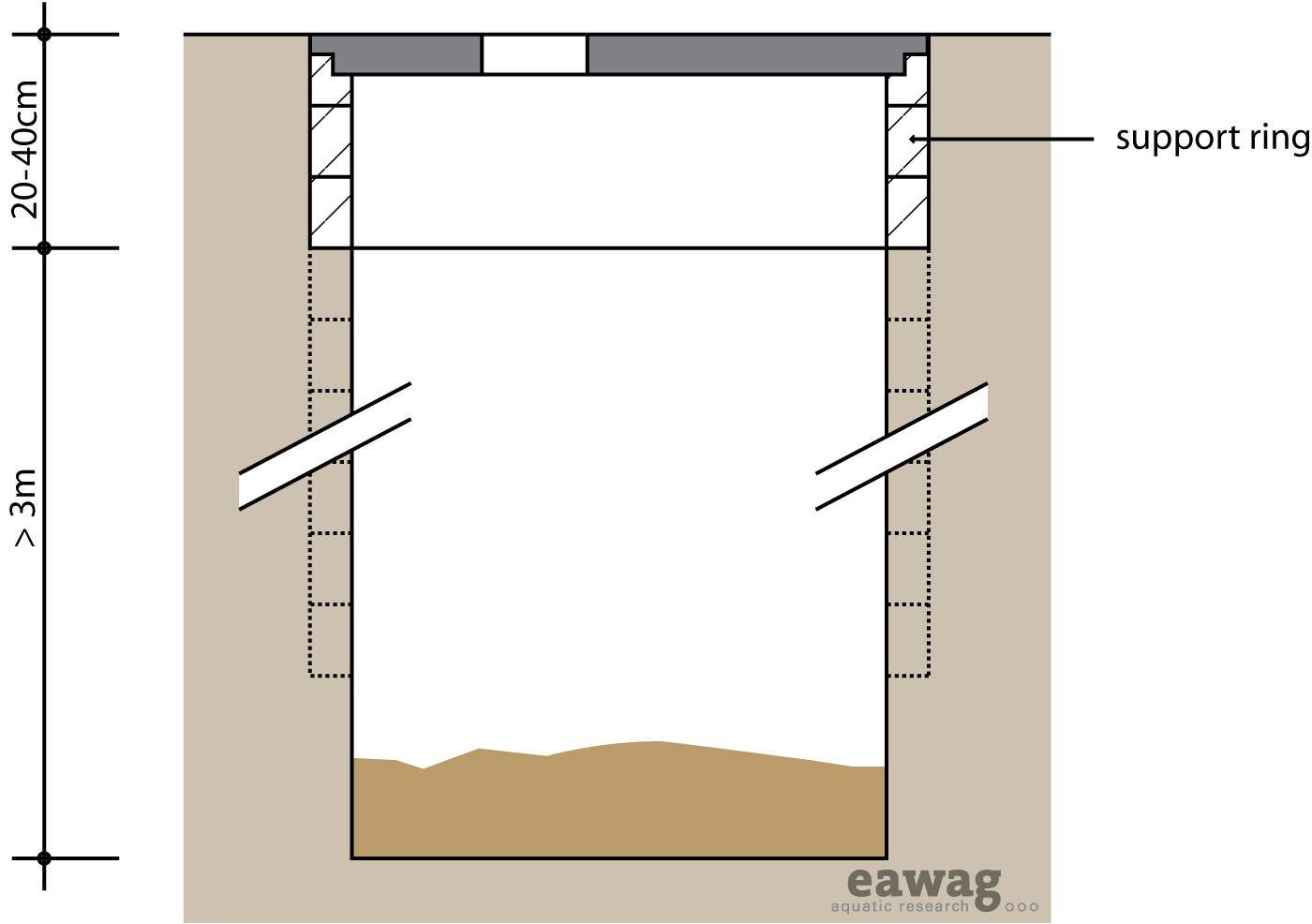

On average, solids accumulate at a rate of 40 to 60L per person/year and up to 90L per person/year if dry cleansing materials such as leaves, newspapers, and toilet paper are used. The volume of the pit should be designed to contain at least 1,000L. Ideally the pit should be designed to be at least 3m deep and 1 m in diameter. If the pit diameter exceeds 1.5m there is an increased risk of collapse. Depending on how deep they are dug, some pits may last up to 20 years without emptying. If the pit is to be reused it should be lined. Pit lining materials can include brick, rot-resistant timber, concrete, stones, or mortar plastered onto the soil. If the soil is stable (i.e. no presence of sand or gravel deposits or loose organic materials), the whole pit need not be lined. The bottom of the pit should remain unlined to allow the infiltration of liquids out of the pit.

As the effluent leaches from the Single Pit and migrates through the unsaturated soil matrix, faecal organisms are removed. The degree of faecal organism removal varies with soil type, distance travelled, moisture and other environmental factors and thus, it is difficult to estimate the necessary distance between a pit and a water source. A distance of 30m between the pit and a water source is recommended to limit exposure to chemical and biological contamination.

When it is impossible or difficult to dig a deep pit, the depth of the pit can be extending by building the pit upwards with the use of concrete rings or blocks. This adaptation is sometimes referred to as a cesspit. It is a raised shaft on top of a shallow pit with an open bottom that allows for the collection of faecal sludge and the leaching of effluent. This design however, is prone to improper emptying since it may be easier to break or remove the concrete rings and allow the faecal sludge to flow out rather than have it emptied and disposed of properly.

Another variation is the unlined shallow pit that may be appropriate for areas where digging is difficult. When the shallow pit is full, it can be covered with leaves and soil and a small tree can be planted. This concept is called the Arborloo and is a successful way of avoiding costly emptying, while containing excreta, and reforesting an area. The Arborloo is discussed in more detail on the Fill and Cover - Arborloo section.

| Advantages | Disadvantages/limitations |

|---|---|

| - Can be built and repaired with locally available materials. - Does not require a constant source of water. - Can be used immediately after construction. - Low (but variable) capital costs depending on materials. |

- Flies and odours are normally noticeable. - Sludge requires secondary treatment and/or appropriate discharge. - Costs to empty may be significant compared to capital costs. - Low reduction in BOD and pathogens. |

Contents

Adequacy

Treatment processes in the Single Pit (aerobic, anaerobic, dehydration, composting or otherwise) are limited and therefore, pathogen reduction and organic degradation is not significant. However, since the excreta are contained, pathogen transmission to the user is limited. Single Pits are appropriate for rural and peri-urban areas; Single Pits in urban or dense areas are often difficult to empty and/or have sufficient space for infiltration. Single Pits are especially appropriate when water is scarce and where there is a low groundwater table. They are not suited for rocky or compacted soils (that are difficult to dig) or for areas that flood frequently.

Health Aspects/Acceptance

A simple Single Pit is an improvement to open defecation; however, it still poses health risks:

- Leachate can contaminate groundwater;

- Stagnant water in pits may promote insect breeding;

- Pits are susceptible to failure/overflowing during floods.

Single Pits should be constructed at an appropriate distance from homes to minimize fly and odour nuisances and to ensure convenience and safe travel.

Upgrading

A Ventilated Improved Pit (VIP) is slightly more expensive but greatly reduces the nuisance of flies and odours, while increasing comfort and usability. For more information on the VIP please refer to the Single Pit VIP page. When two pits are dug side-by-side, one can be used while the contents of the other pit are allowed to mature for safer emptying. For more information on dual pit technologies refer to Double Pit VIP and Twin Pits for Pour Flush pages.

Maintenance

There is no daily maintenance associated with a simple Single Pit. However, when the pit is full it can be a) pumped out and reused or b) the superstructure and squatting plate can be moved to a new pit and the previous pit covered and decommissioned.

Field experiences

| Akvo RSR Project: Ensure access to safe water and sanitation

Salinity, arsenic, lack of proper IWRM, and incidence of natural disasters in the three districts of the Southwest coastal belt of Bangladesh cause a lot of socioeconomic and health related problems. The programme is right-based and strengthens knowledge and capacity of community WASH groups as well as local government institutions. As problems are multifaceted, the programme uses a multi-pronged strategy and facilitates partnership with existing institutional stakeholders relevant for WASH sector. |

References

- Brandberg, B. (1997). Latrine Building. A Handbook for Implementation of the Sanplat System. Intermediate Technology Publications, London. (A good summary of common construction problems and how to avoid mistakes.)

- Franceys, R., Pickford, J. and Reed, R. (1992). A guide to the development of on-site sanitation. WHO, Geneva. (For information on accumulation rates, infiltration rates, general construction and example design calculations.)

- Lewis, JW., et al. (1982). The Risk of Groundwater Pollution by on-site Sanitation in Developing Countries. International Reference Centre for Waste Disposal, Dübendorf, Switzerland. (Detailed study regarding the transport and die-off of microorganisms and implications for locating technologies.)

- Morgan, P. (2007). Toilets That Make Compost: Low-cost, sanitary toilets that produce valuable compost for crops in an African context. Stockholm Environment Institute, Sweden. (Describes how to build a support ring/foundation.)

- Pickford, J. (1995). Low Cost Sanitation. A Survey of Practical Experience. Intermediate Technology Publications, London. (Information on how to calculate pit size and technology life.)

Acknowledgements

The material on this page was adapted from:

Elizabeth Tilley, Lukas Ulrich, Christoph Lüthi, Philippe Reymond and Christian Zurbrügg (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies, published by Sandec, the Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries of Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

The 2nd edition publication is available in English. French and Spanish are yet to come.